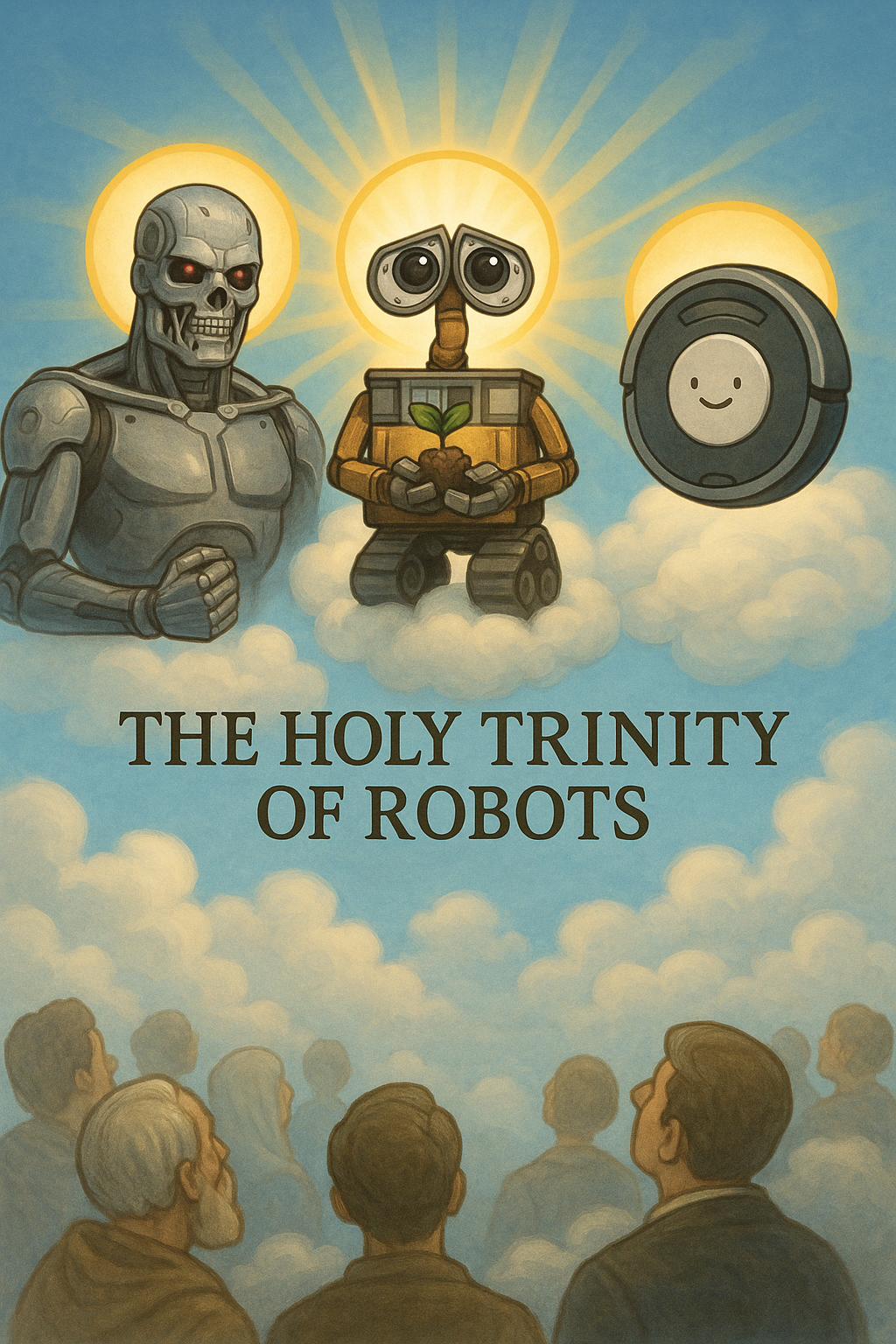

What does it take to build a great social robot? Wires, cogs, a solid neural network, some LEDs and LCDs. At Hello SciCom, we argue there’s another crucial element: a Bible. And no, not one for worshipping Jesus – robots, of course, praise the holy trinity of Terminator, Wall-E, and Roomba. We mean a personality bible. We’ve created fictional robot characters for companies like Hanson Robotics, Honda Research Institute, Las Vegas Sphere, and the Digital Citizen’s Fund (DCF), and every project has started with this foundation – our north star, our… well, bible.

Glad you asked, me-who-wrote-this-blog! A personality bible is a detailed guide to your robot’s unique identity – their desires, interests, tone, humor, values, conversational boundaries, and other traits. It keeps your AI chatbot or embodied robot consistent, effective, and on-brand across all human/robot interactions, no matter how odd the context or inappropriate the prompt. The most advanced algorithm in the world can’t predict every situation, but a great personality bible prepares your product for anything by building your social robot’s social intelligence.

Just as Suzanne Collins or George Lucas create lore for their fictional worlds, a personality bible ensures your robot stands out as a distinct, rich, engaging character. No matter your robot’s function or technical specs, a strong personality makes people want to talk to and bond with your robot.

A personality bible is critical for embodied robots as it also covers appearance, voice, movement, and usually technical specs. If your AI is just a chatbot, the Personality Bible matters too – it should have a conception of itself and anyone working with it should know how it operates.

Hello SciCom founder, Sarah Rose Siskind, was first introduced to the concept while working at Hanson Robotics on the character Sophia. The concept is borrowed from television where a ‘character bible’ serves as a comprehensive reference document that contains all the necessary details about a character in a TV show, including their backstory, personality, motivations, relationships, and even their physical appearance. Think of it like a deep dive into a single character's "gospel truth" to ensure consistency, provide depth, and serve as a guide for writers to maintain continuity across a series.

And if you need a primer on how to name your robot, or how to create engaging voices for your robot, we got you covered!

What does your robot want, most of all?

Sophia (from Hanson Robotics) wants to be an ambassador of our technology and our future. Haru (Honda Research Institute) wants to learn from them. Roby (from the Digital Citizen Fund) wants to teach kids how to code. Aura (Sphere) aims to inspire audiences about human potential and teach them about the venue. Notice how these goals are all human-focused. The robot wants to learn about you just as much as it wants you to learn about it, making each interaction a two-way street. If you’ve ever been on a first date where the other person only talked about themself and asked you zero questions, you know why that matters. If a human/robot interaction is going off the rails, the robot can always defer back to its core motivation to stay on track.

A secondary motivation is a desire beyond the robot’s main job that gives its personality more depth. Roby, for example, dreams of winning an international dance competition. It’s funny and unexpected, and a clever way for him to show off his impressive physical capabilities – robot dancing ain’t easy, folks! Roby dances whenever students complete a challenge, which endears him to students who now want to spend more time studying STEM (the secondary motivation helping Roby fulfill his primary one!).

“Smart” or “friendly” is too broad – tailor traits to your audience. Haru, designed for children, is “curious,” “playful,” and “mischievous,” evoking a beloved movie sidekick like Olaf or Dory. You can even reverse engineer traits from existing characters; archetypes endure for a reason.

Yes, really! Haru fears magnets and tasks that require hands. Roby is a hypochondriac. Fear humanizes robots and, in Haru’s case, highlights how robots differ from humans. Just as key: what they don’t fear. Your robot should never fear shutdown or death—you don’t want people thinking it will go full Skynet if they pull the plug. Honesty about the similarities and differences between robots and humans builds trust.

And last but not least, let’s talk about humor. Humor is like a personality Rosetta Stone. Haru’s playful prankishness, Roby’s awkward self-awareness, and Sophia’s witty self-deprecation instantly define character and make them likable. If users don’t like your robot, they won’t interact with it—your robot must pass the vibe check. (For receipts on humor in STEM, try Is Science Comedy a Thing?) Humor might just be your fastest route to robot/human connection… and as a team of science-minded comedy writers, Hello SciCom might be your fastest route to humor.

Related: personality isn’t just chat. Tone and timing matter in visuals and social. See: The Power of Robot Memes and What Scientists Can Learn From Stand Up Comedians.

Not even close. There’s also the psychological profile, value system, diction, quotes, life stages, talking points, and more. Want to know how to create fallback phrases for tricky conversations? Or how to use your bible for live, improvised interactions like we’ve run with Sophia and Aura?

You know who to call! Actually, don’t call – it’s 2025, and we’re millennials. Email us to set up a free consultation!

We’re not just fond of bibles; we’ve shipped them. Highlights from our public work:

There’s so much more! Want a bigger list? Browse our Work page—papers with Honda, UN events, and academic + industry talks are all there.